The Melting Pot of Biryani

How a layered-rice dish is symbolic of the multicultural nature of the Mughal Empire. And what it can teach us about South-Asian harmony today.

Introduction

Biryani is a dish with a long and rich history, dating back to the time of the Mughlai empire. The dish is a mix of many different cultures and traditions, and this is reflected in its name; ‘Biryani’ is derived from the Persian word ‘biryan’, meaning ‘fried or roasted’. The earliest references to zerbiryans, or Biryani-like dishes, can be found in the 16th century Akbar Nama. Shah Jahan’s cookbook also contains a recipe for a layered rice dish, which is thought to be the precursor to modern-day Biryani.

With its roots in Persian and Indian cuisine, Biryani as a dish is truly reflective of Mughal-era multiculturalism. This aspect of its history gives it great historical significance as a symbolic uniting factor for the vast and diverse Mughal empire.

Biryani is a prime example of how the merging of cultures can result in a new and unique dish. The dish has been able to retain its popularity over the centuries because it is able to appeal to a wide range of people. Biryani is typically made with rice, meat, and a variety of spices. The exact ingredients and proportions vary depending on the region and historical time-period where it is made.

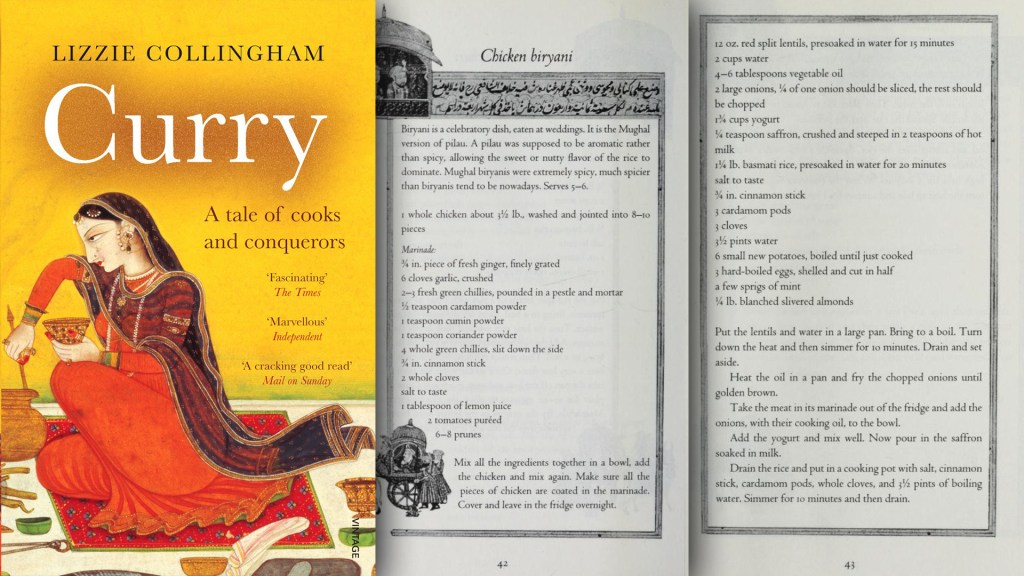

In Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors, Elizabeth Collingham, argues that biryani was a the result of the marriage of Indian and Central Asian cuisines. She states that biryani is a “rice dish that originated in Persia, but which was popularized in India by the Moghul rulers”. Collingham’s argument is backed up by the fact that biryani is made with meats and spices that were common in Mughal cuisine.

Biryani is a representation of Mughal multiculturalism as it is a dish that is a fusion of Persian and Indian cuisine. The Mughals were a tolerant and inclusive empire, and this is reflected in their cuisine. The dish is a reflection of the cosmopolitanism of the Mughal rulers, who were open to accepting new cultures and influences, rather than just imposing their own ideals.

Malar Gandhi, in the essay “Tracing the History of Biryani” notes that Indian cuisine as a whole is a blend of cultures of many invaders: the Turks, Arabs, Persians, and Afghans. While the Turks and Arabs brought many new ingredients to India, such as tomatoes, potatoes, and eggplants, it was the Persians and Afghans who really helped to shape Indian cuisine. They introduced spices such as cardamom, cloves, and poppy seeds, as well as methods of cooking such as using clarified butter (ghee), all of which form the basis of Biryani.

The Mughals raised cooking to an art form, introducing several recipes to India like biryani, pilaf, and kebabs.

This essay does not aim to discover or define the first biryani, rather, the underlying assumption is that the dish was a constantly evolving and still is to this day, based on local ingredients and tastes. From a historical perspective, however, the Biryani of the Mughal court was emblematic of the multiculturalism that the empire was based on.

History

Collingham writes that biryani was first mentioned in literature in the 13th century, and she notes that it has been popular in India for centuries. She briefly discusses the history of biryani and how it has been adapted by different cultures over time. Over the centuries, various regions of India developed their own unique versions of biryani. In the north, where the influence of Persian cuisine was strong, dishes tended to be more lightly spiced. The earliest known mention of a dish similar to biryani comes from the 9th century Persian book Kitab al-Tabikh. This book contains a recipe for a layered rice called the Maqlooba.

Akbar

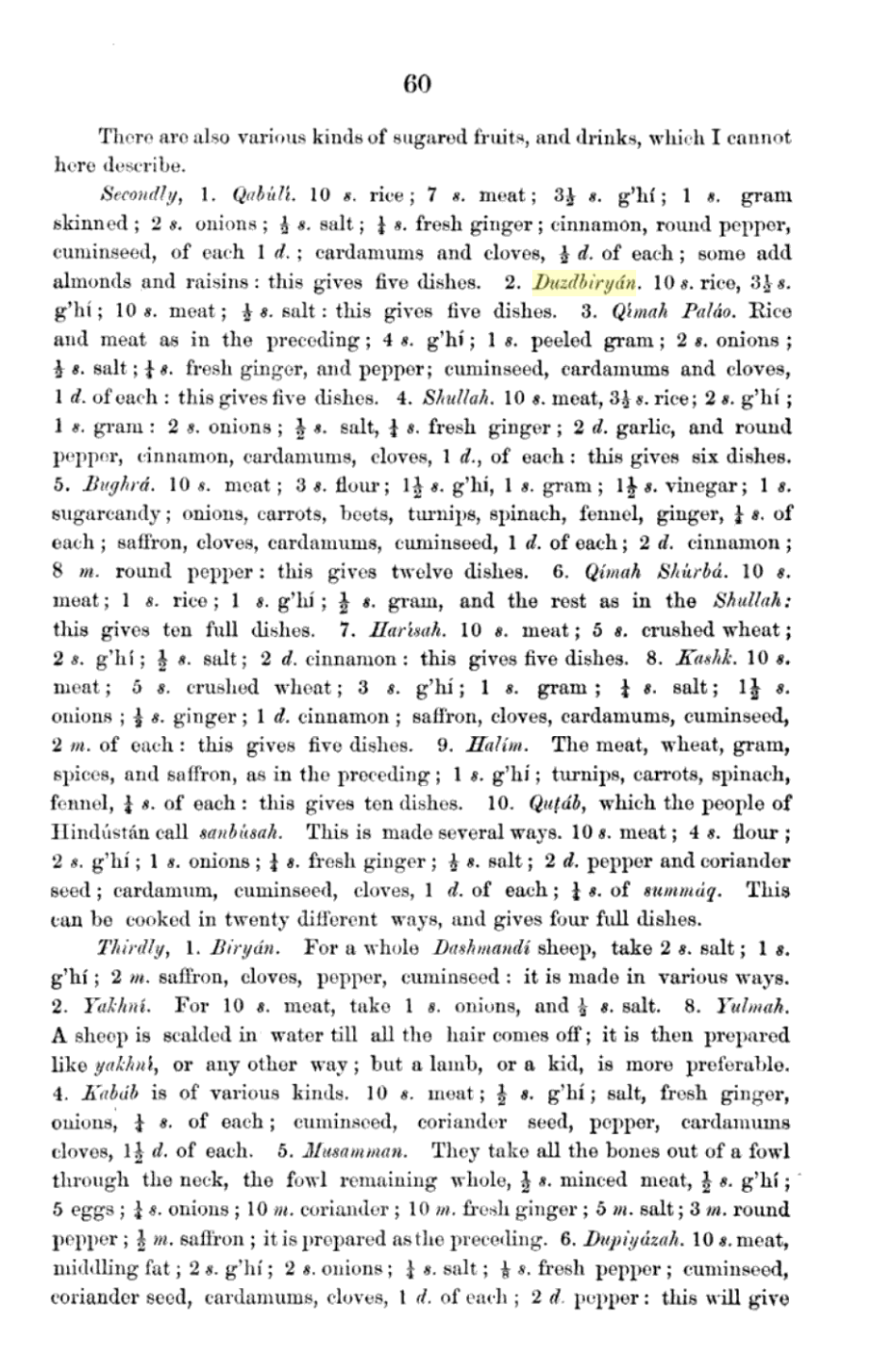

Historical references to Biryani date back to Akbar’s time. One of the most famous references to biryani is in the Ain-i-Akbari, a 16th-century document that chronicles Akbar’s reign, written by Mughal court advisor Abu’l-Fazl ibn Mubarak. The document makes mention of ten dishes that use rice and meat together. In it he mentions “Duzdbiryán“, likely a precursor to modern-day biryani.

What is more relevant to our thesis is how simple this recipe is in comparison to the recipes that the preceding emperors had. This recipe calls for rice, ghee, meat and salt. This shows us a rudimentary precursor to Biryani that had not yet been influenced by Indian cuisine.

Shah Jahan

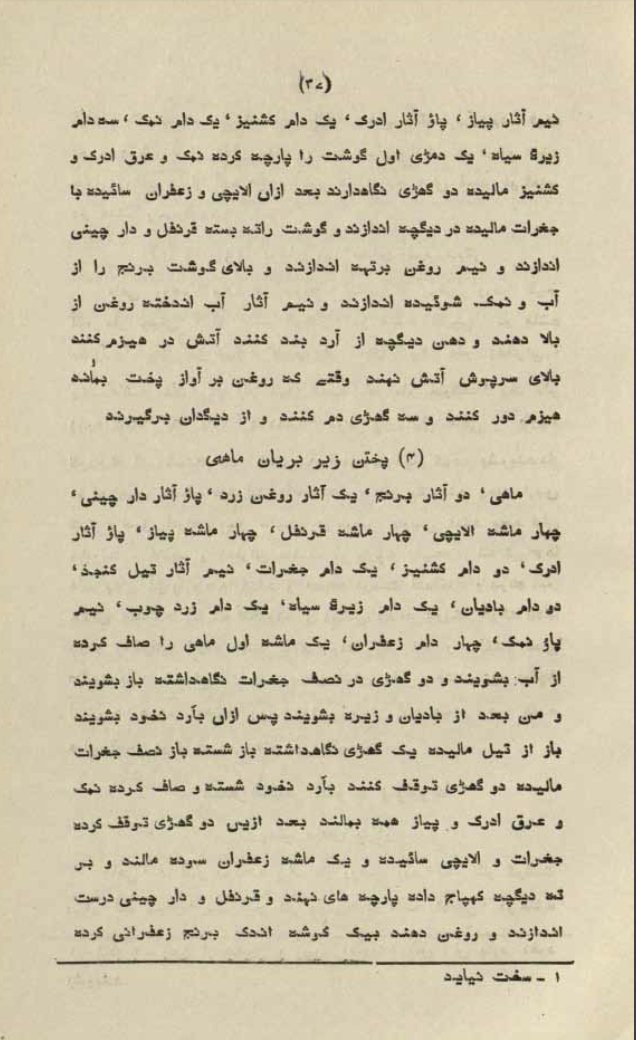

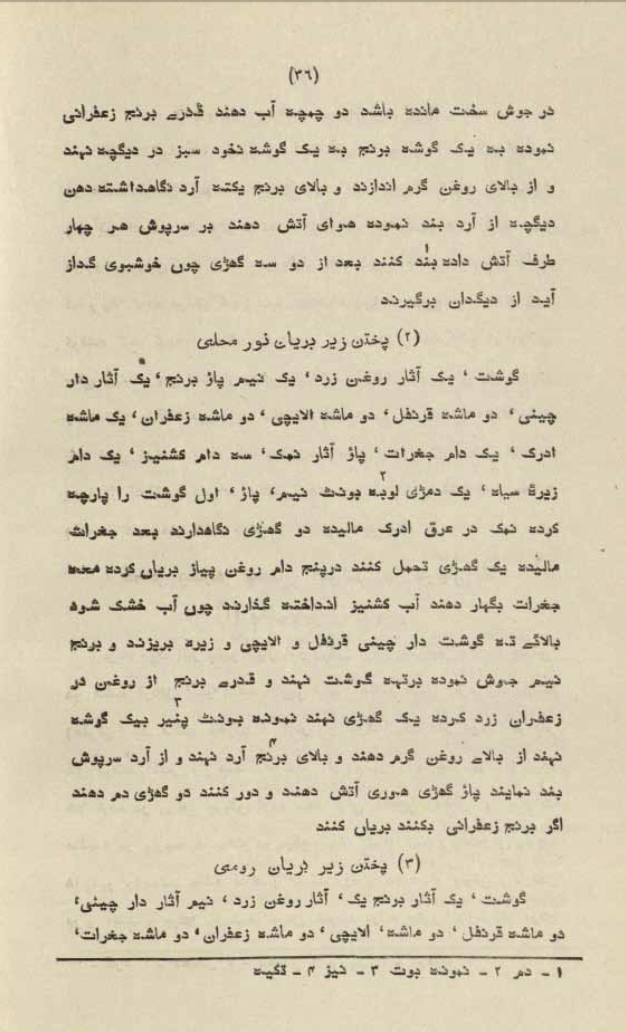

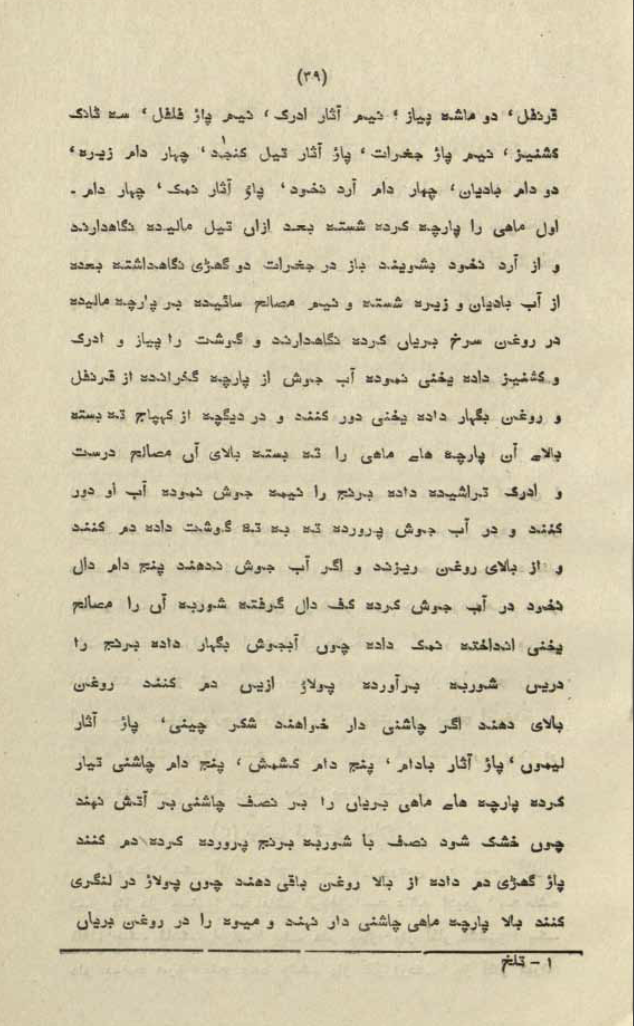

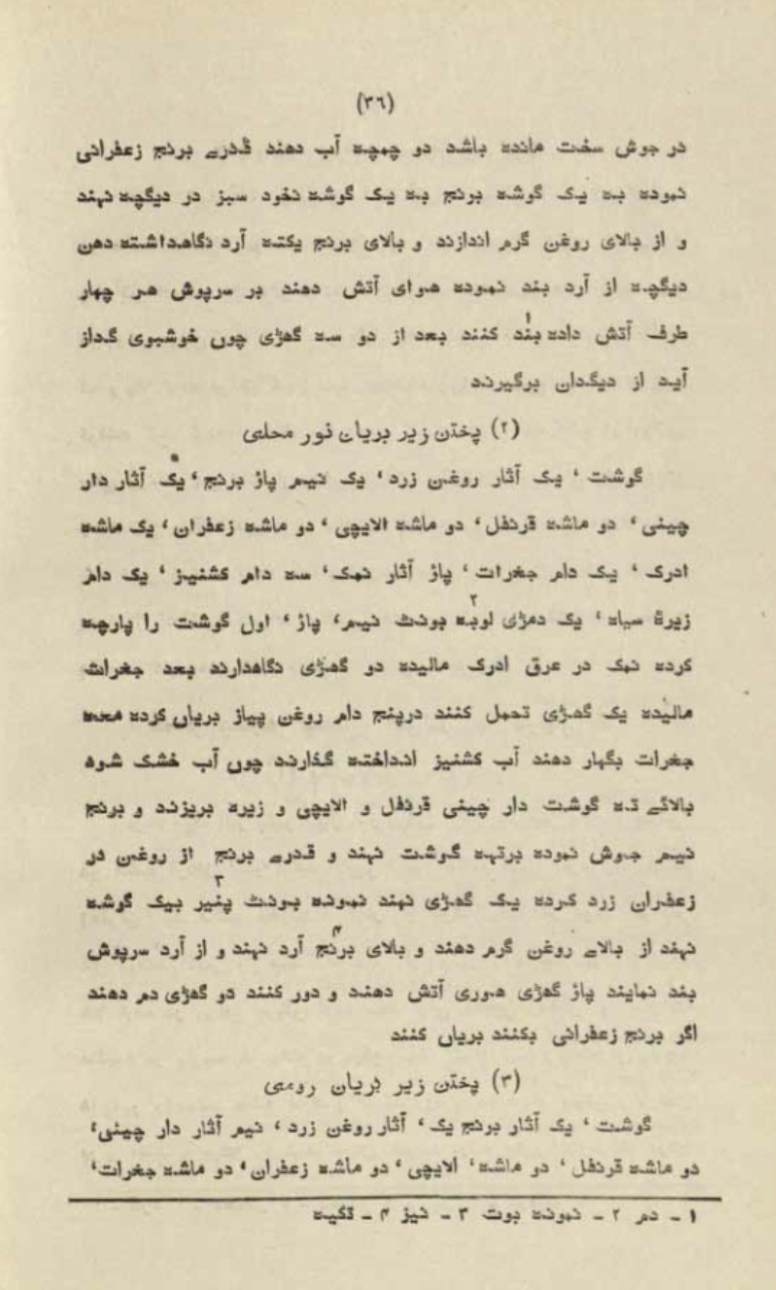

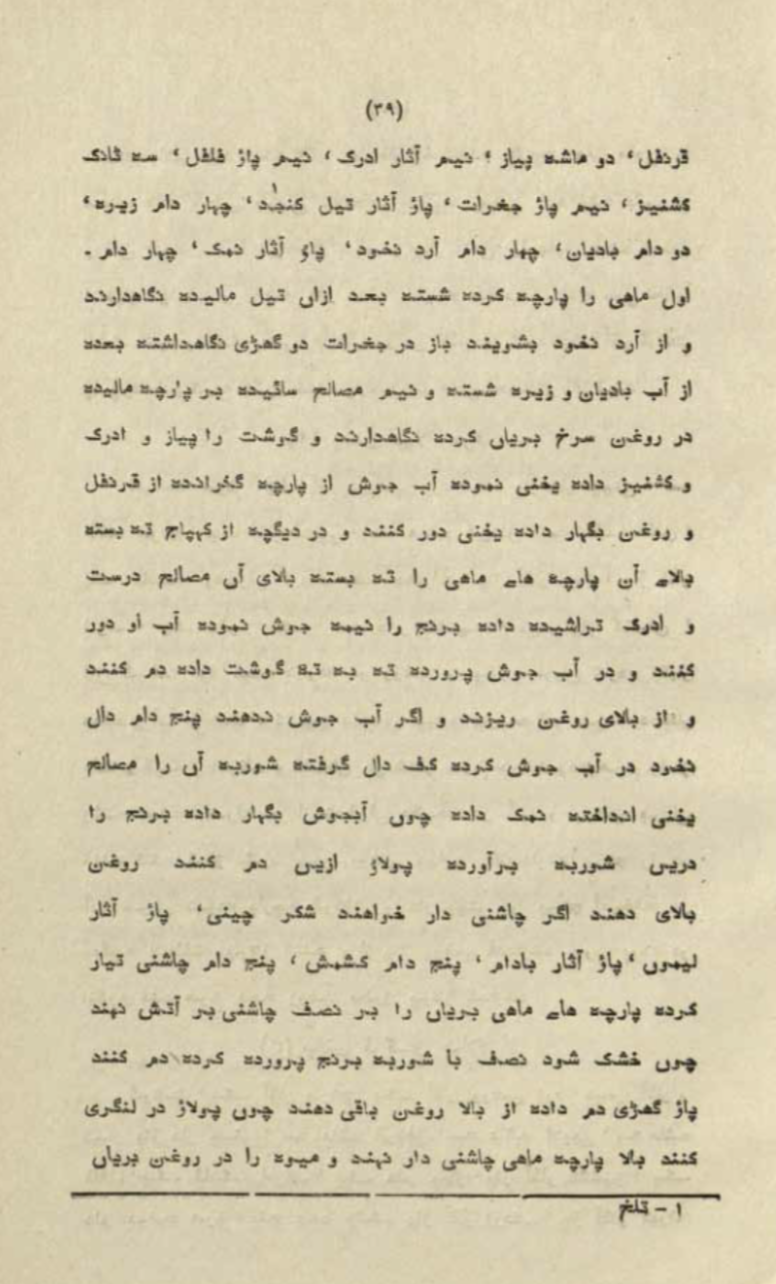

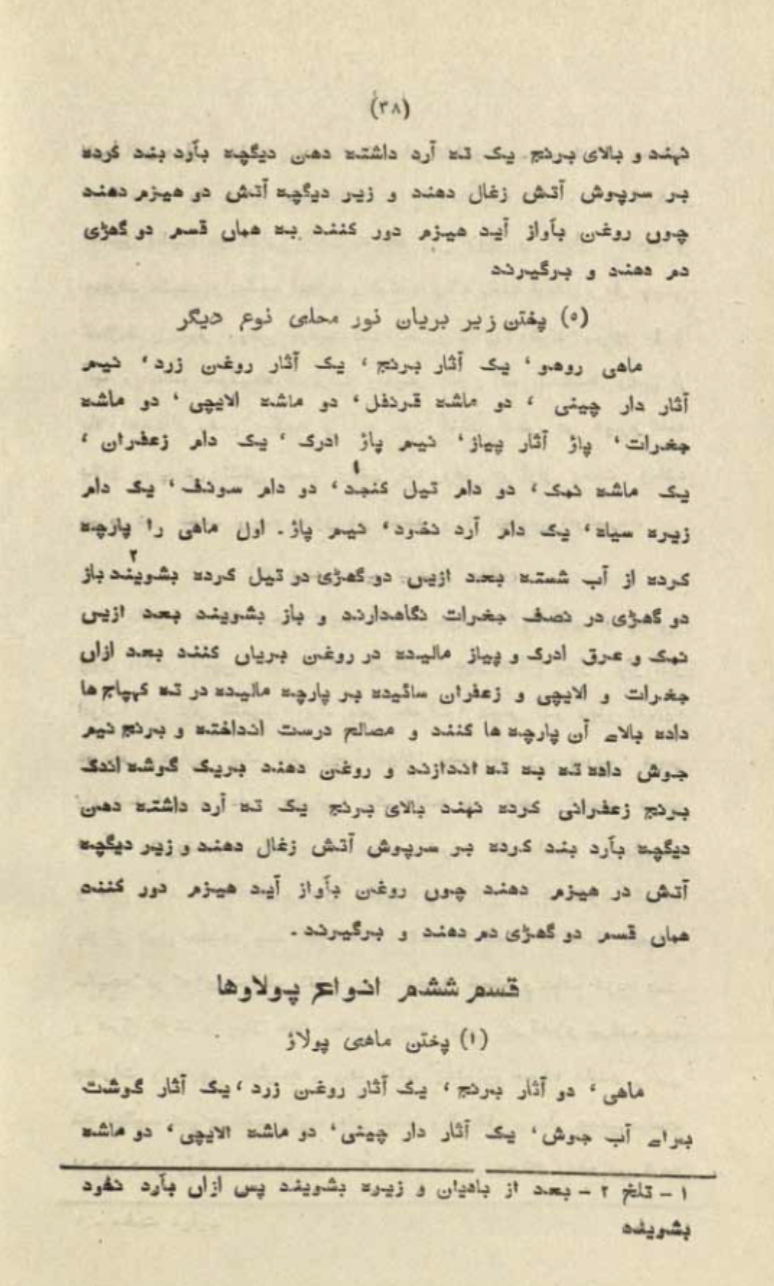

Shah Jahan, the fifth ruler of the Mughal Empire from 1628 to 1658, and during his reign, biryani became a popular dish in the empire. In his cookbook, Nuskha-e-Shah Jahani, there is an entire chapter dedicated to different styles of biryani with detailed recipes. It also contains several recipes for biryani, including one that is very similar to the modern-day dish. There are also references to biryani being served during religious festivals and ceremonies, which further attest to its popularity at that time. Shah Jahan was particularly fond of biryani and one of the special recipes for it includes saffron, cardamom, and other expensive spices.

Aurangzeb

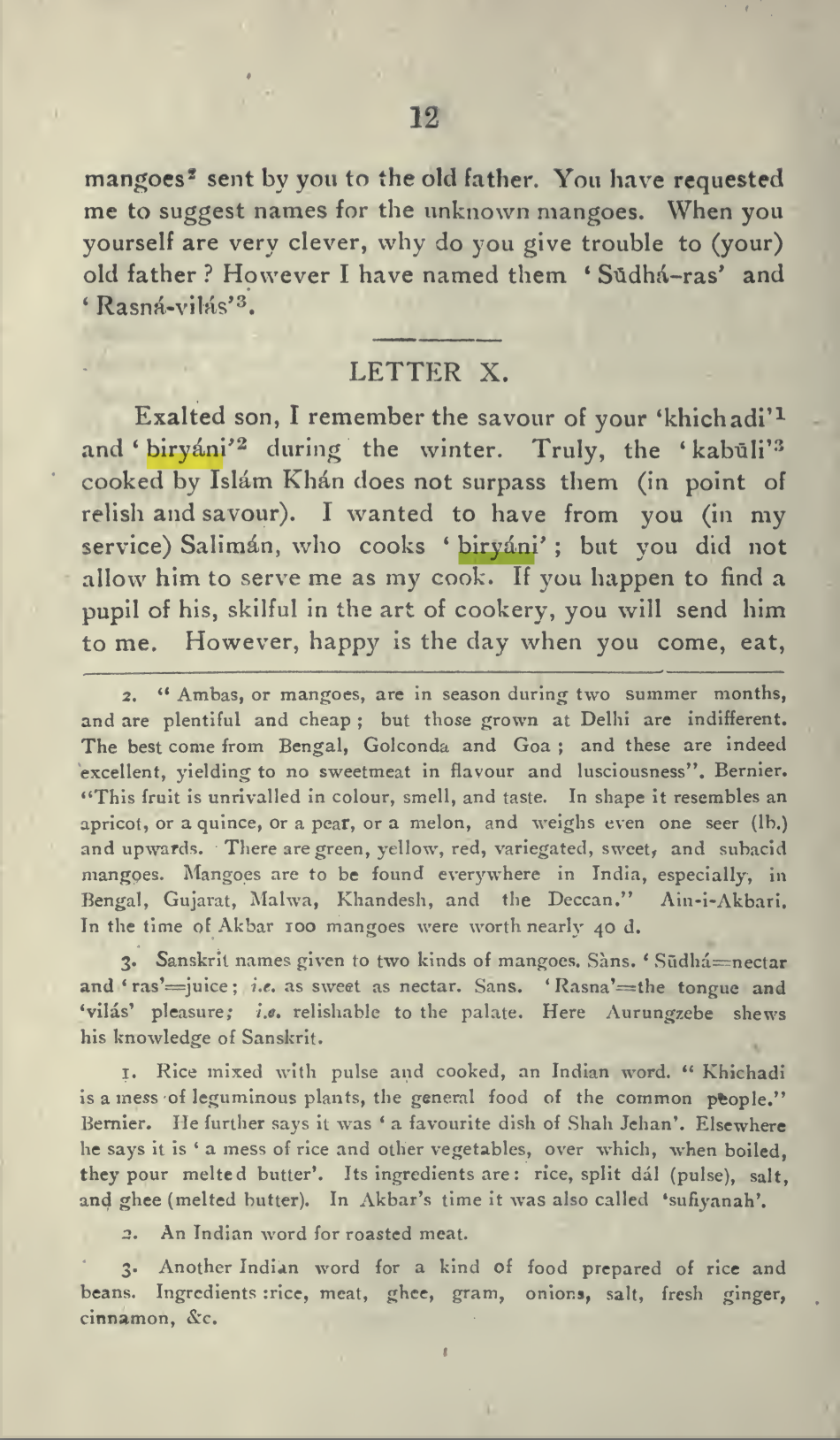

Rukat-e-Alamgiri is a collection of recipes by the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb compiled through various letters. It contains a recipe for Birinj-al-Safawi, a rice and meat dish that was popular at the Mughal court. Birinj-al-Safawi is made with lamb or chicken, rice, spices, and dried fruits. Aurangzeb was known for his love of simple food, and he often wrote to his son and Wazir, Dara Shikoh, asking for Qubooli rice to be sent to him while he was on his campaigns. These are recorded in Rukat-e-Alamgiri as well.

Exalted son … I wanted to have from you (in my service) Saliman, who cooks ‘biryani’; but you did not allow him to serve as my cook. If you happen to find a pupil of his, skillful in the art of cookery, you will send him to me.

Bilimoria, Ruka‛at-i-Alamgiri

Representation of Multiculturalism

Multiculturalism in the Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was a powerful and influential force in the Indian subcontinent for centuries. The empire was characterized by its multiculturalism, with a diverse set of cultures, religions, and customs coexisting and interacting with each other. Different cultures and religions coexisted and contributed to the empire’s rich tapestry throughout the centuries. The empire’s art, poetry, and language reflected this diversity, and its cuisine was a fusion of different culinary traditions.

According to the The Akbarnama of Abu-L-Fazl, the emperor’s multicultural policy was based on the principle of Sulh-i-kul, a notion of achieving absolute peace through inter-religious dialogue and tolerance (Beveridge, 1902). This was done through a multitude of practices which included the abolition of the Jizya Tax, allowances for the construction of all religious buildings, and multi-religious discussion groups. In these groups, representatives of Muslims (of Sunni, Shia, and Sufi traditions), Hindus (Shaivite and Vaishnavite), Christians, Jains, Jews, and Zoroastrians came together to discuss and understand their differences and commonalities. There was also a party of atheists represented in the discussion: the skeptical Charvaka School, dating back to 6th century BC, which denied the very existence of God. (Sen, 2005).

As a result, there was a great deal of interchange and synthesis between different cultures in the empire which extended beyond just the cuisine. For instance, Mughal art incorporated elements from both Islamic and Hindu traditions, creating a distinctive style that was loved by rulers and commoners alike. The Persian language, which was the language of the Mughal court, also absorbed words and phrases from Hindustani, the language spoken by the general population.

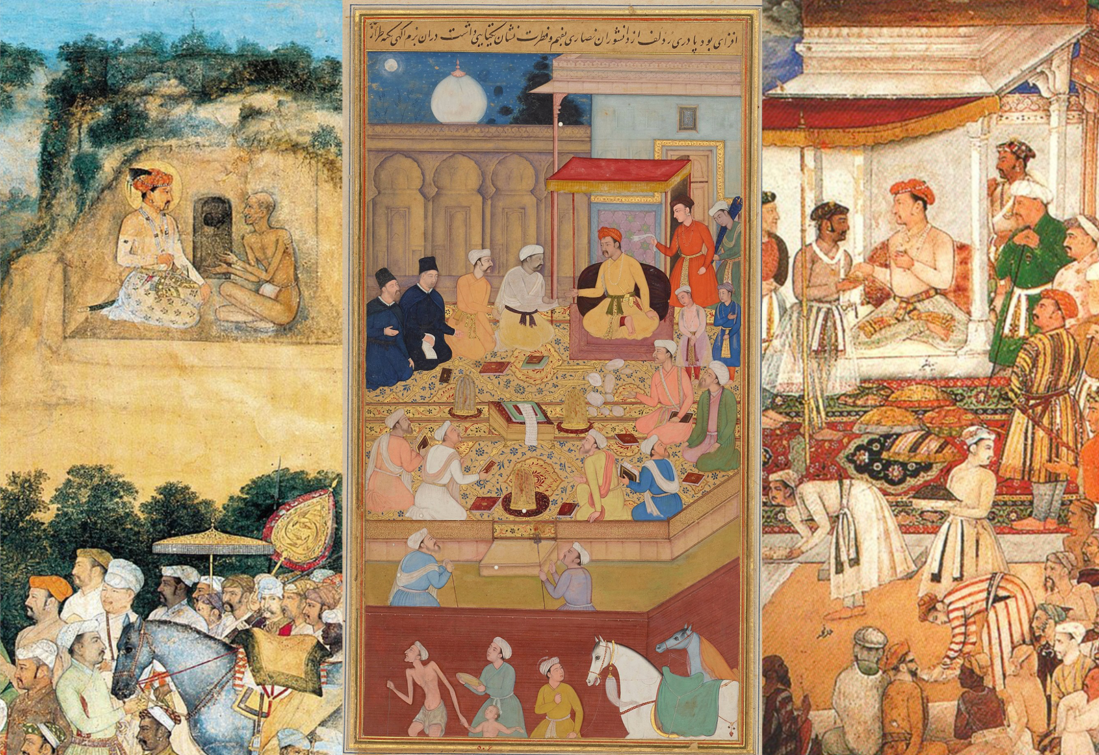

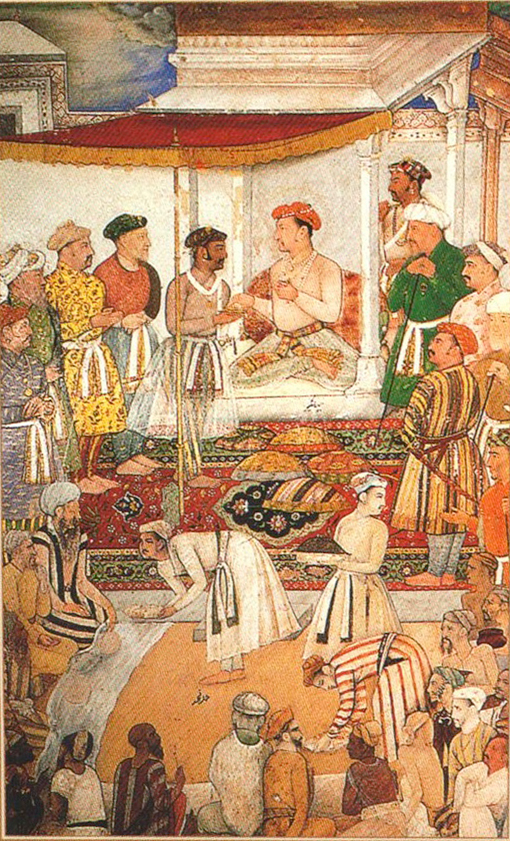

The miniature on the right shows Mughal Emperor Akbar (r. 1556-1605) holding a religious assembly in the Ibadat Khana (House of Worship) in Fatehpur Sikri. (Nar Singh, 1605, Akbarnama)

Blending of Cuisines

Mughlai food, royal cuisine of the Mughals, is often thought of as a blend of different cultures and customs. The cuisine has its roots in Central Asia, but over time it has been influences by the cuisine of the Middle East, Persia, and India. The power of the Mughal emperors and the spread of their empire ensured that Mughlai cuisine dominated in Northern India.

Arjun Appadurai tells us, that it had emerged out of a combination of Turko-Afghan culinary traditions with the ‘peasant food of the North Indian plain’. This new hybrid cuisine then made its way from the royal courts to different parts of India, all the way to Bengal. Along the way regional ingredients created yet more variations.

Pre-Mughal era ‘Indian’ cuisine itself was very diverse. So the new Mughal cuisine was not only influenced by Muslim traditions, but also by the traditions of the Hindus and Afghans among other regional groups. For example, many Mughal dishes are cooked in ghee, a type of clarified butter that is used in Hindu cuisine.

Food as a uniting factor

Food was an important tool for the Mughals in maintaining control over their sprawling empire. The Mughals were masterful at using food to create harmony between different cultures and religions. By incorporating the cuisine of the conquered people into their own, the Mughals were able to create a sense of commonality between the various groups that made up their empire.

Collingham reveals that Jahangir discovered Gujarati khichari while traveling around his empire, something the Mughals did a great deal to remind their subjects of their power and authority. When they traveled, the imperial kitchen traveled with them. It is the custom of the court when the king is to march the next day, then at ten o’clock of the night the royal kitchen should start…Fifty camels and 200 coolies, with baskets on their heads, were needed to carry the supplies. By traveling around their empire, the Mughals incorporated the cuisines of their subjects into the Mughlai cuisine.

The Mughals were also tolerant of different religions and cultures, and this tolerance was reflected in their cuisine. Muslim, Hindu, and Buddhist influences can all be seen in Mughal cooking. This tolerance extended to the way the Mughals prepared their food. Halal, kosher, and vegetarian options were all available, depending on the preferences of the diner. Recipes for a biryani based on paneer (cottage cheese used commonly as a protein source) can be seen in the start of the biryans chapter in Shah Jahan’s cookbook.

Food was used by the Mughals to bring people of different religions and cultures together. By celebrating the best of each culture’s cuisine, the Mughals were able to create a sense of unity amongst their people. This unity was essential to the Mughals’ success as an empire.

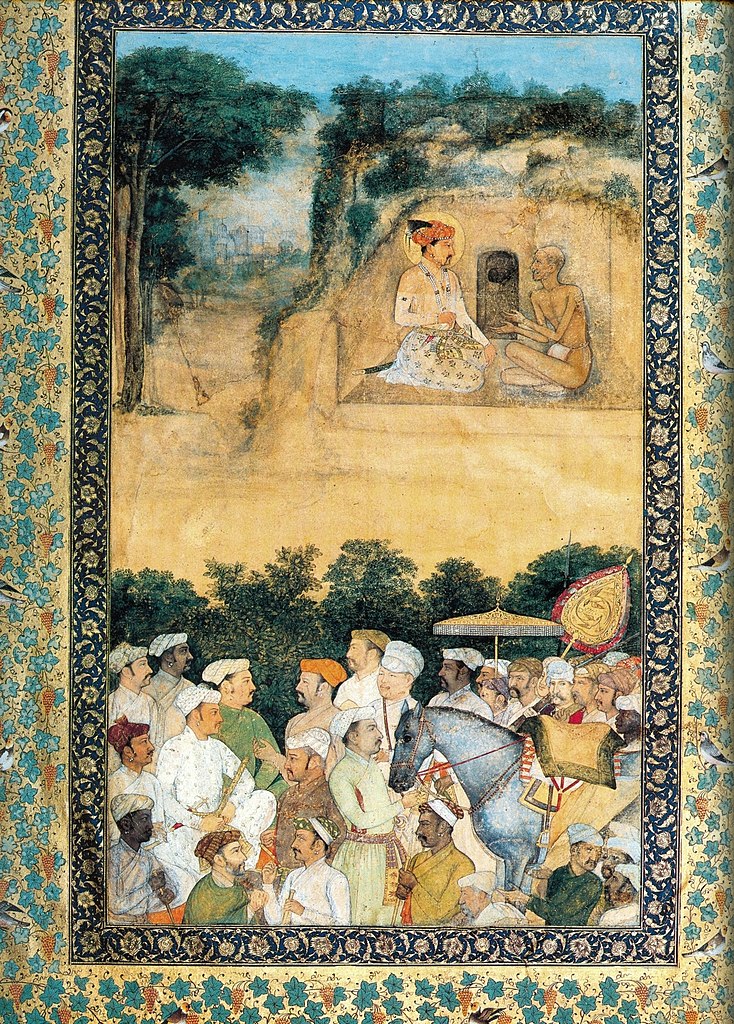

The painting on the right shows Jahangir visiting a a Hindu ascetic, Jadrup– a perfect embodiment of the harmony of faiths seen in pre-British India.

Significance of Biryani

The current variations of biryani represent the multicultural harmony of the Indian subcontinent, with each region adding its own unique twist to the dish. There are many differences in biryani found in Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh. Each region has its own unique version of this popular dish, which is often made with rice, meat, and vegetables. In Pakistan, biryani is often made with lamb or chicken, while in India, it is more common to find versions made with beef or shrimp. Bangladeshi biryani is often made with fish or vegetables. However, the similarities are still there: layering of the long-grained rice, use of a plethora of spices and a curd mixture to marinate the meat.

Biryani is a representation of multiculturalism in Mughal India because it is a dish that incorporates ingredients and cooking techniques from many different cultures and time periods.

From the royal courts of the Mughals to a global icon of Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi food, with current variations just as diverse as the story of its inception, Biryani is an embodiment of the rich cultural heritage of the Indian subcontinent.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Jahangir dispensing food at Ajmer – Jahangirnama c. 1620 National Museum of India

ibn Mubārak, A. A. F. (1873). The Ain i Akbari. Asiatic Society of Bengal.

Fazlulla, S. M. (1956). Nuskha-e-Shah Jahani (No. 136). Government oriental manuscripts library.

Bilimoria, J. H. (1908). Ruka’at-i-Alamgiri; or, Letters of Aurungzebe.

Beveridge, H. (Trans.) (1902/2010). The Akbarnama of Abu-L-Fazl, Volumes I, II and III.

Akbarnama, miniature painting by Nar Singh, ca. 1605

Background Sources

Gandhi. (2011). Tracing the History of Biryani. India Currents Magazine, 25(2), 42–.

Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors, Elizabeth Collingham

Sen, A. (2005). The Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian History, Culture and Identity. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Narayanan, D. (2015). Cultures of Food and Gastronomy in Mughal and post-Mughal India (Doctoral dissertation).

Antani, V., & Mahapatra, S. (2022). Evolution of Indian cuisine: a socio-historical review. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 9(1), 1-15.

Secondary Sources

Appadurai, A. (1988). How to Make a National Cuisine: Cookbooks in Contemporary India. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 30(1), 3-24. doi:10.1017/S0010417500015024

Banerjee-Dube, I. (2018). Modern Mixes: The Hybrid and the Authentic in Indian Cuisine. In: Choukroune, L., Bhandari, P. (eds) Exploring Indian Modernities. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-7557-5_9

Mukherjee, S. K., & Das, A. K. Culinary Tourism in Kolkata: A Study on Kolkata Biryani. Local Food and Community Empowerment through Tourism, 71.

Antani, V., & Mahapatra, S. (2022). Evolution of Indian cuisine: a socio-historical review. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 9(1), 1-15.

Mangalassary, S. (2016). Indian cuisine—the cultural connection. In Indigenous culture, education and globalization(pp. 119-134). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Rana, N. K. (2022). The Perpetual Quest for ‘Authenticity’in Indian Cuisine: An Answer through History and Folklore. Digest: A Journal of Foodways and Culture, 9(1).